News

Family uses tragedy of daughter’s car crash in Weld County to promote seat belt use

Tad Johnson pored through his daughter’s Facebook photos the morning after she died in an automobile crash and thought about how, even at 19, she wanted to own a business — maybe a hair salon.

He read comment after comment about her desire to help others when they seemed to need her the most.

Tad was proud of her own determination and devotion to others and, many times, he would wake up at 2:15 a.m. and think to himself how lucky he was to have her call him Dad.

But as he clicked through selfies of her behind the wheel, his grieving shifted to frustration and anger.

Alexa’s death should have been prevented, he thought.

“That student-to-student and peer-to-peer messaging is so important. They all use the social media. They could give us lessons.”

— Jona Johnson, mother of Alexa Johnson

Sure, the white Ford 150 pickup truck she was driving careened off Interstate 25 at highway speeds, but there wasn’t that much damage to the truck.

When emergency crews arrived, they could still open all four doors.

Instead of taking four seconds to buckle up, she kept the clip clicked while she sat in front of the belt, tricking the on-board safety system that blares an obnoxious beep to deter unrestrained driving.

As Tad went through more photos, he realized they all showed a teenage girl beaming with glee but never with a belt draped across her shoulder.

Angry at himself for never catching his daughter’s blunder and angry at friends for never stopping it, Tad pounded out a Facebook post blasting everyone who failed to shame her into wearing her seat belt.

Then he took a breath, hit delete, and wrote a plea to her circle of friends to drive carefully and think of 19-year-old Alexa whenever they fastened their seat belts.

He posted it, and it wasn’t long before hundreds of friends and family liked, shared and commented on it.

That was the “ah-ha” moment when he and his wife, Jona, realized the reach of social media sites like Facebook.

The post he wrote reached audiences they never imagined possible, and it would be just the beginning.

Like a growing number of people afflicted by tragedy, the Johnsons were awestruck by the power of social media in wake of tragedies, and they realized they had an opportunity to be more than a grieving family who lost a child in a vehicle crash on Weld County roads.

They had a chance to prevent other families from feeling their pain.

AMID TRAGEDY EMERGES HOPE

Tad and Jona’s nightmare started with a crazed ring of a doorbell and a dog named Patches that was yelping relentlessly.

Amid a sea of early February darkness, the two fumbled their way around their Loveland home and rushed toward the front door where a flashlight’s beam shined through the door’s glass window.

Tad figured something tragic must have happened, even before the Colorado State Patrol officer said a word.

“The longest walk I ever took was from that front door to that couch,” he says from the couple’s dining room table. He points across the open living room toward the door, re-living the somber 20-foot trek he took with the trooper. “I already knew.”

The grieving process began instantly, and the days painfully ticked by as the family arranged funeral services and tried to comprehend life without Alexa’s energy.

She had recently graduated from Loveland High School and was working at car sales shops in the area, yet remained available at all hours of the day to help a friend.

That’s where she was heading Feb. 10 when, shortly after 2 a.m., her truck left the southbound lanes of Interstate 25 between the Johnstown and Berthoud exits, rolled over and ejected her.

“The nights are the hardest when you’re grieving,” he said. “The night is when you’re alone. It’s just you and the dead silence. It was very therapeutic for me to go through her photos.”

Among the things Tad and Jona missed most about Alexa was the embrace of her hug.

Every time the couple would drive somewhere, they would think about how differently things could have been if Alexa was still alive or had worn her seat belt properly.

And every time they pulled the strap across their shoulders, they thought of it as a hug from their daughter.

Seeking a way to blend Alexa’s story with a seat belt awareness campaign, they created Alexa’s Hugs.

From their home, they would craft decorated pieces of ribbon and velcro that people could place on their seat belts to remember her — it was like her hug.

The goal was just to keep her memory alive but, through the powers of social media, the campaign’s popularity exploded.

Friends started posting photos of themselves wearing the ribbon. Companies started sponsoring concert ticket raffles or gas money that would be awarded to someone who posted a photo of a buckled seat belt and a ribbon.

Interest grew. Local newspaper and television stations featured the campaign — stories that were shared across the country. The months crept by, and the orders for hugs kept growing and growing as more and more people learned about them through Facebook.

Tad got a call last spring from a woman who lived in an extremely rural town just a stone’s throw from the Canadian border in North Dakota. The woman had seen a Colorado news story that was shared via social media, and she wanted to give ribbons advocating seat belt safety to her area’s entire high school graduating class — all 13 students.

Coupled with calls from people in virtually every state requesting the home made hugs, the success of the program that had gone viral was enough to bring Tad and Jona to tears.

They knew they were onto something big. It’s still enough to make them break down in tears of joy, though they admit they sometimes get worried they won’t be able to keep up with the demand for the hugs.

In the 11 months that have ticked by since Alexa died, the Johnsons have handmade nearly 3,400 ribbons.

More than 1,000 of those have gone to students across schools in the Thompson Valley School District, and thousands of others have gone out to people around the country.

“We are learning about the power of social media by doing what we’re doing. We know how necessary it is. Everything is so quick now,” Tad said with the snap of a finger.

MESSAGES AND MEMORIALS SEEN AROUND THE WORLD

Just like the Johnsons, Sharon and Steven Heit wanted to keep their son’s memory alive, and they’ve seen first-hand how quickly a safe driving message can spread.

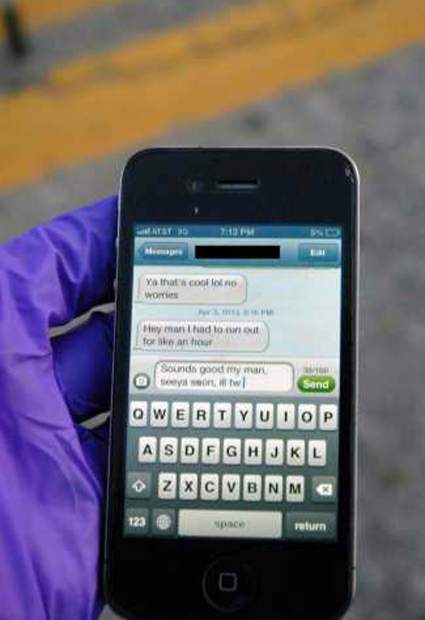

In the days after their 19-year-old son, Alexander, lost control of the vehicle he was driving and flipped along O Street in Greeley, the Heits released through the Greeley Police Department an image of the text message he had been distracted by.

The response and acclaim that followed was beyond what they had ever envisioned, they explained in a recent email to The Tribune.

They had hoped local media outlets would run with the message: “NEVER text and drive.” Then the calls started streaming in from outlets across the country, and the image even appeared in news publications in London.

It was difficult at first for the Heits to think of any good coming from their son’s tragic death, but they were encouraged by how quickly the word got out and how effective the image was.

“Friends, family members and strangers have written to us saying they place now their phones in the back seat of their cars so they won’t be as tempted,” the couple wrote in an email, adding that it probably would have been impossible for such connection 10 — or even five — years ago.

“We hope that this idea catches on, and that forever more, phones will take a backseat to driving,” they said.

Beyond public awareness campaigns that can become wildly successful in an instant, Facebook has revolutionized how people grieve and even learn about a tragedy in their inner circle.

Whether it’s through a post on a high school class-of page announcing someone had died or a friend simply posting a photo of a crash he or she was involved in, the instant communication over tragedy has changed things.

Plus, it revolutionizes how people can stay informed about someone’s condition after a crash.

Mariah Motschman was involved in a crash that on Aug. 15 killed three other passengers a few miles south of the Wyoming border.

In the days and weeks that followed, family and friends flooded Facebook and online fundraising sites to help fund the medical bills stemming from a broken neck, back and jaw.

It’s a story that has become increasingly common in today’s fast-paced world. Some people share a memory. Some share a prayer. Others just watch. But there’s a sense of community and connectivity that previously went unmatched.

OUT OF DARKNESS, LIGHT EMERGES

Tad Johnson is walking along the dark highway that is illuminated only by passing headlights, and he asks himself “what am I doing here?”

Then, he realizes what’s about to happen. He watches his daughter’s entire crash unfold in front of him, but he’s unable to catch her.

He wakes up from the reoccurring nightmare, screaming. That helpless feeling is one that he can’t shake, but with the reach of Alexa’s Hugs, he knows he might be able to prevent other parents from experiencing their own personal nightmare or at least help them through it.

Since then they’ve continued to push their message of seat belt awareness and have taken on a new campaign in schools — a program they hope to bring into Weld County schools that includes a public speaking push and contest among schools to increase their own seat belt use and even create a public service announcement addressing the issue.

“They will be sharing messages with their other school mates about not just seat belts but vehicle safety,” Jona said from the same table where she spends a huge chunk of the day working with the soon-to-be fully-licensed nonprofit. “That student-to-student and peer-to-peer messaging is so important. They all use the social media. They could give us lessons.”

It’s part of their continued march toward their goal of dropping accident rates across northern Colorado.

It’s a very possible goal, they say, pointing to the promise of peer-to-peer connections. The kids have to want the changes. In a lot of ways, social media is the perfect way to bridge that gap.

Despite the couple’s runaway success with Alexa’s Hugs, they still suffer.

In the days following the crash, Tad came close to ripping the door bell out of the wall. The sound was too much of a trigger of that night in February when the trooper stood at the doorstep. They’ve since disconnected it and placed a piece of tap over the outside button.

Digging through boxes of Christmas decorations was difficult, especially when they came across the hand-made ornaments they painted as a family.

To this day, Jona said, she sometimes finds a toe sock that Alexa clung to just one year ago.

And then there’s those Facebook photos of her without a seat belt, from which an encouraging thing has happened.

Alexa’s friends who admitted to previously driving unbuckled have changed their ways and even champion safe driving, occasionally posting a photo with their personalized Alexa Hug.

Tad and Jona still find those online photos therapeutic, and they love seeing friends posting others.

But it’s the collection of dozens of printed shots that are stuck on the side of the refrigerator that they look toward more these days.

Some are school pictures and professional portraits from her teenage years, but others are childhood family memories depicting mischievous kids and quirky smiles. They’re the photos that make scrapbooks come to life.

The photos face the dining room table where almost all of the work for Alexa’s Hugs happens.

In that regard, she’s always there. That helps, but Tad and Jona still hurt when they think about how different things could of been.

“It’s knee-buckling,” he said, “to walk by her photo and at that moment realize that we’ll never have an opportunity to take another.”

Reporter Jason Pohl covers cops, courts and public safety issues for The Tribune. Follow him on Twitter @pohl_jason.

Read the Greeley Tribune article